Stimming: Why do Autistic people need it?

What purpose does stimming serve? Is it something we should be trying to stop? What should we do if stimming becomes harmful? This piece answers those questions.

When thinking about core characteristics shared by Autistic people, I would suggest that nothing is as prominent as stimming. Stimming, or "self-stimulatory behaviour" shares an intimate relationship with Autistic experience.

"Stimming or self-stimulating behaviour includes arm or hand-flapping, finger-flicking, rocking, jumping, spinning or twirling, head-banging and complex body movements.

It includes the repetitive use of an object, such as flicking a rubber band or twirling a piece of string, or repetitive activities involving the senses (such as repeatedly feeling a particular texture)."

National Autistic Society (2020)

Stimming is often reduced to physical motions or vocalisations. In fact, we can stim using any of our senses. One that has been spoken about in particular on this website is interoceptive stimming (Gray-Hammond & Adkin, 2023). We can stim off of emotions and internal bodily feelings in the same way we might with hand flapping or vocalisations. While stimming is widely talked about in Autistic spaces, the question in wider society remains; why do Autistic people stim?

What are the benefits of stimming for Autistic people?

There is no singular benefit of this particular behaviour in Autistic people. It should also be noted that it is not unique to Autistic people, but certainly appears to be a more frequent occurrence for Autistic people (Oroian et al, 2024; Charlton et al, 2021). There are however some notable benefits of stimming;

Emotional Regulation and Expression

Stimming may be used as a way of not only expressing emotions, such as the flapping of a child's hands when excited, but also as a way of regulating emotions. Autistic people can often experience alexithymia (Gray-Hammond, 2023), presenting a challenge to how they respond to emotions. Research has suggested that stimming allows Autistic people to regulate and relax, or even distract from negative emotions, experiencing more positive emotional outcomes (Charlton et al, 2024; McCarty & Brumback, 2021; Petty & Ellis, 2024).

Sensory Regulation

The sensory experience of being Autistic in the world can be imagined as a ship in unpredictable and dangerous seas. Stimming provides an anchor that allows Autistic people to take a moment without the fear of drifting into catastrophe. Sensory experiences can be traumatic (Fulton et al, 2020). Stimming allows us to exercise autonomy in unpredictable and traumatic environments. By initiating a sensory experience, we are better able to cope with other sensory information (Charlton et al, 2024; McCarty & Brumback, 2021; Petty & Ellis, 2024).

Increased Bodily Awareness

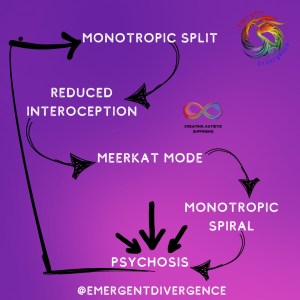

Autistic people can often struggle with bodily awareness, likely due to differences with proprioception and interoception (Armitano-Lago et al, 2021; Hatfield et al, 2019). Some Autistic stims may actually help increase our awareness of our body (Petty & Ellis, 2024). This is interesting when considering the community created concept of the "burnout to psychosis" (Adkin & Gray-Hammond, 2023) cycle which features reduced interoception, allowing us to posit that increased body awareness may reduce negative mental health outcomes.

Enjoyment

Stimming is not purely functional. It can also be something performed for enjoyment and pleasure. Much int he way someone might sing when they are on their own, Autistic people may stim because they like and enjoy the way it makes them feel (Petty & Ellis, 2024).

Why we shouldn't suppress stimming

When an Autistic person is not allowed to stim, we are taking away an important tool for their healthy engagement in the world (McCarty & Brumback, 2021). One paper describes the suppression of stimming as being similar to holding back words that you desperately need to say (Charlton et al, 2024). From a personal perspective, not being allowed to stim feels similar to holding your breath for too long. It becomes a source of distress and panic. Autistic people widely reject the suppression or behavioural elimination of stimming (Kapp et al, 2019).

Not all stimming is positive

It's important to note at this point that some stims can be injurious or otherwise harmful. From head-bang, to biting, to skin picking. Distressed Autistic people can hurt themselves in the attempt to cope with difficult experiences and emotions. It has also been discussed on this website how substance use behaviours can be related to harmful stimming (Gray-Hammond, 2024).

Unfortunately harmful stims are highly stigmatised, particularly in children (Marsden et al, 2024) often being used as examples of why stimming should be eliminated. Community spaces actually tend to recommend that the more helpful thing to do in these situations is establish what purpose the stim serves, particularly from a sensory perspective, and to redirect it into a healthier stim that provides a similar feedback.

Why we need to be okay with Stimming

Ultimately, this is a matter of somatic liberty. We have to recognise that people, regardless of neurocognitive style or perceived level of disability, have the right to bodily autonomy. Neurotypically performing people can probably relate to other issues surrounding bodily autonomy, but may not necessarily understand this situation. Being told how to embody yourself, down to the subtle movements, noises, and sensory experienced you have is deeply traumatic. When we teach our children not to stim, we teach them to be alienated from their bodies. We teach them that their bodies do not belong to them. I, personally, think that claiming ownership of another's body is one of the most harmful things we can do.

References

Adkin, T. & Gray-Hammond, D. (2023) Creating Autistic Suffering: The AuDHD Burnout to Psychosis Cycle- A deeper look. Emergent Divergence. Retrieved from https://emergentdivergence.com/2023/06/05/creating-autistic-suffering-the-audhd-burnout-to-psychosis-cycle-a-deeper-look/

Armitano-Lago, C., Bennett, H. J., & Haegele, J. A. (2021). Lower limb proprioception and strength differences between adolescents with autism spectrum disorder and neurotypical controls. Perceptual and motor skills, 128(5), 2132-2147.

Charlton, R. A., Entecott, T., Belova, E., & Nwaordu, G. (2021). “It feels like holding back something you need to say”: Autistic and Non-Autistic Adults accounts of sensory experiences and stimming. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 89, 101864.

Fulton, R., Reardon, E., Kate, R., & Jones, R. (2020). Sensory trauma: Autism, sensory difference and the daily experience of fear. Autism Wellbeing CIC.

Gray-Hammond, D. (2023). What is alexithymia? Emergent Divergence. Retrieved from https://emergentdivergence.com/2023/06/30/what-is-alexithymia/

Gray-Hammond, D. (2024). Interoception and Autism: A Hidden Link to Substance Use? Emergent Divergence. Retrieved from https://emergentdivergence.com/2024/05/21/interoception-and-autism-a-hidden-link-to-substance-use/

Gray-Hammond, D. & Adkin, T. (2023) Creating Autistic Suffering: Interoceptive Stimming or "challenging behaviour"? Emergent Divergence. Retrieved from https://emergentdivergence.com/2023/09/18/creating-autistic-suffering-interoceptive-stimming-or-challenging-behaviour/

Hatfield, T. R., Brown, R. F., Giummarra, M. J., & Lenggenhager, B. (2019). Autism spectrum disorder and interoception: Abnormalities in global integration?. Autism, 23(1), 212-222.

Kapp, S. K., Steward, R., Crane, L., Elliott, D., Elphick, C., Pellicano, E., & Russell, G. (2019). ‘People should be allowed to do what they like’: Autistic adults’ views and experiences of stimming. Autism, 23(7), 1782-1792.

Marsden, S. J., Eastham, R., & Kaley, A. (2024). (Re) thinking about self-harm and autism: Findings from an online qualitative study on self-harm in autistic adults. Autism, 13623613241271931.

McCarty, M. J., & Brumback, A. C. (2021, July). Rethinking stereotypies in autism. In Seminars in pediatric neurology (Vol. 38, p. 100897). WB Saunders.

National Autistic Society. (2020). Stimming - a guide for all audiences. Retrieved from https://www.autism.org.uk/advice-and-guidance/topics/behaviour/stimming/all-audiences

Oroian, B. A., Costandache, G., Popescu, E., Nechita, P., & Szalontay, A. (2024). Comparative analysis of self-stimulatory behaviors in ASD and ADHD. European Psychiatry, 67(S1), S220-S220.

Petty, S., & Ellis, A. (2024). The meaning of autistic movements. Autism, 13623613241262151.